When we think of tricksters, we generally imagine folk characters and culture heroes, not gods. Tricksters either tend to be associated with animal spirits (such as Coyote), or are Promethean figures, archetypal "humans" who interact with and upset the world of the gods. But one of the world's greatest and most interesting trickster figures is not only a god, but a god of high metaphysical content. He is Eshu-Elegbara, one of the orisha, the West African deities that are worshiped in many related forms across African and the African diaspora in the New World.

While he embodies many obvious trickster elements — deceit, humor, lawlessness, sexuality — Eshu-Elegbara is also the god of communication and spiritual language. He is the gatekeeper between the realms of man and gods, the tangled lines of force that make up the cosmic interface, and his sign is the crossroads. In the figure of Eshu-Elegbara, the West African tradition makes a profound argument about the relationship among spiritual communication, divination, and the peculiar chaotic qualities of the trickster. But before we investigate Eshu-Elegbara's character, we must first place him in the general context of orisha worship.

Meet the Living Gods.

Th orisha, the gods of the Fon and Yoruba peoples of West Africa, are some of the most vital and intriguing beings ever to pass through the minds of men and women. The orisha are profoundly "living" gods, if by this we means archetypes, or constellations of images and forces, that actively permeate the psychic lives of living humans. On the simplest level they are alive because they are worshiped: orisha are prayed to, invoked, and ritually "fed" by many millions of people in both Africa and the Americas. Not only are the gods alive, but they are long-lived; unlike contemporary Neo-Pagan deities, which have basically been reconstructed from the inquisitional ashes of history, the orisha have been passed through countless generations of worshipers with little interruption.

More profoundly, the very nature of the orisha is to be alive in the most fundamental sense we know — though our own human lives. Though they possess godlike powers, the orisha are not transcendent beings, but are immanent in this life, bound up with ritual, practice, and human community. They are accessible to people, combining elements of both mythological characters and ancestral ghosts. Like both of these groups of entities, the orisha are composed of immaterial but idiosyncratic personalities that eat, drink, lie, and sleep with each other's mates. Though West African tradition does posit a central creator god, he/she is generally quite distant, and the orisha are, like us, left in a world they did not create, a world of nature and culture, of sex, war, rivers, thunder, magic, and divination. The orisha are regularly "fed" with animal blood, food, and gifts, and during rituals the gods frequently possess the bodies of the faithful. Their behavior draws from the full range of human experience, including sexuality, mockery, and intoxication.

That the orisha remain outside the scope of many Western students of esotericism and even polytheism is understandable, given the historical domination of Africans by the Europeans of the New World. Black Americans were forced to hide their deities or dress them up in Catholic garb, while whites cut themselves off from all but the most superficial appreciations of those African cultural values that managed to survive. To even graze the heart of the orisha, white Westerners must overcome two obstacles: the storehouse of Hollywood's cartoon representations we carry in our subconscious, and the more pernicious underlying Western prejudices against traditional African worship, which run the gamut from the denigration of blood sacrifice to the absurd notion that polyrhythm is somehow less sophisticated and more primitive than European musical forms.

But why bother? As one esotericist I spoke to put it, "Why be interested in these grotesque and parasitic deities?" One could answer that these gods are fascinating, vibrant, and unique, and serve as a window onto the spirit and culture of Africa and the black traditions that have had a major influence on New World culture. More to the point, however, they are not grotesque but rich in character; they are not parasites, but entities deeply and reciprocally bound up with the daily lives of their worshipers. When we look on West Africa, we must keep in mind that our "instinctive" sense that these alien practices are primitive, savage, and even demonic is the lingering afterimage of thoroughly European and colonialist images of tribal Others dancing in the hot jungles of sexuality, atavism, and perversion. Looking toward Africa, the first thing the West encounters is its own dark mirror.

The fact that people tend to simplify images of pre-colonialist Africa — for example, imagining simple villages where there were vast, cosmopolitan city-states replete with bureaucrats, poets, and sewer systems — is only one indication of the lingering tendency to see Africa as the repository of the primitive. Even when looking seriously at West African spiritual traditions, white Westerners run into two potential traps: the error of seeing such systems as purely traditional and not historically dynamic; and the temptation to idealize tribal peoples and project onto them some prelapsarian harmony with Nature, a condescending and overly romantic error rampant, for example, in the New Age embrace of Native American spirituality.

Because the West is such a text-oriented culture, there is an understandable tendency to equate civilization with the technology of writing, and the sort of reflective interior consciousness that that particular machine apparently constructs in human beings. West Africa did not possess writing as we now it, and the orisha disclose themselves not in books but in shrine, ritual, and memory. For today's text-oriented seeker, there are no great Yoruba books to commune with, no Gita or Genesis. Though the Yoruba system of divination, Ifa, compares to the I Ching in terms of complexity, strucutre, and poetic sublimity, few know about it outside the tradition, partly for the simple reason that the "writing" of Ifa is carried in the heads of the diviners, the babalawo.

But the images of West African spirituality that come most immediately to mind in Western culture are images of ritual possession. Though many esotericists have a sympathy for invocation and strong ritual, the performance of West African possession remains bracing, far different from the bloodless, "spiritualized" rituals of monotheisms, or from the almost literary rituals of modern, reconstructed Neo-Paganism. Possession by the orisha is a visceral fact. To the intensely exciting yet coolly controlled beating of drums, the possessed person (usually a dancer; in Haitian parlance, the "horse" who is to be "ridden") shakes, falls on the ground, rolls his or her eyes, perhaps froths at the mouth, and speaks in different voices. The particular orisha is recognized by his or her mannerisms, is costumed appropriately in ritual rooms, and proceeds to prophesy, dance, ask for food or booze, and if it's Eshu, may start pawing the ladies. I have attended Haitian voudun rituals, but even from photographs and film it is clear from the eyes of the possessed person that a qualitatively different order of consciousness and personality has momentarily annexed the everyday persona, which invariably recalls almost nothing of the experience.

In its rituals, the West African tradition has learned to plug people directly into the realm of archetypes, archetypes which are strengthened by interfacing with the "lower" traits of ordinary human personalities. One clue to the nature of this interchange lies in the fact that possession often seems to be triggered by the master drummer playing particular patterns within the complex web of polyrhythmic drumming. Haitians calls these jarring, rhythmically "dissonant" patterns cassés (or "breaks," a phrase used in a similar musical sense in today's hip-hop culture). Possession may result from the cognitive dissonance of the cassé, the alien beat that enters from another plane and shakes up up the rhythms of the everyday. In any case, possession is a magnificently strange act, a radically immanent embracing of spiritual being that is both magical (a worldly invocation of spirits) and religious (as a selfless release to godhead). Possession by the orisha concretizes spirit and ties it to the cycle of ancestors and blood and the rhythms of sex and family.

So too is blood sacrifice, the "feeding" of the orisha, an acute acknowledgement of the material dimension of spirit, of the fact that it is humans, not gods, that keep gods alive, and that our being is bound up with the excesses of mutual contract and exchange. Molly Ahye, an important scholar of Trinidadian dance as well as an orisha worshiper, speaks about how one "must have the blood, which is a life force, which spirit lives on. You think that spirit doesn't need sustenance, but spirit needs sustenance" (Ahye admitted, however, that she did not kill animals herself).

Even if we cannot accept possession or animal sacrifice, we err in seeing the orisha as being merely superstitious products of animism, or as folk heroes elevated to the level of gods. The orisha are highly evolved archetypal patterns, and they work out metaphysical problems in the heart of life. They form a network, a living and evolving system of forms and forces that from certain angles resonates deeply with the perennial philosophy of the West.

And at the interstices of this network is the Yoruba deity Eshu-Elegbara (or Eshu for short), perhaps the world's most sophisticated Trickster figure (a very similar figure, Legba, exists among the Fon in neighboring Benin). More than a well-hung culture hero (though he's that too), Eshu is a divine mediator of fate and information, a linguist, a crafty metaphysician. Eshu is a trickster not just because he fools people and creates chaos, but more profoundly because he's always escaping the codes of the he simultaneously reinforces. He gives the world the divination system of Ifa, but does not rule over its poetic prophecies, because he is always flowing through the cracks of fate. Eshu fully embodies the sophisticated metaphysics of West Africa, a metaphysics of change and communication, of the copulation between being and world, of the complex power of the crossroads. Eshu expresses a spiritual principle of connection, and the chaos and trickiness of exchange. That he is a god, with stories and moods and lusts, only shows that in the West African tradition, spiritual principles are most real when they're brought into the fabric of daily life, of the recognizably human patterns of money, family, sex, power, and language.

The Hermetic Linguist

Of all European pagan deities, Hermes is the one most closely aligned with Eshu. Like Hermes, Eshu is the divine messenger, and relays information between the gods and between humans and the gods. A small, very dark man, he walks with a large staff, and is often sucking on a pipe, candies, or his fingers. He the "roadmaker;" he "sets the affairs of the earth in order,...is so swift that he can be the messenger for many,...[and] can circle the earth in an instant."[1] Eshu's caprice, quickness, and agility of body and mind are all characteristics he shares with Hermes, perhaps reflecting the perennial spiritual characteristics of communication.

Because Eshu is the messenger, in orisha rituals (today performed from Nigeria to Rio to Montreal) one must "feed" or call him first, before any other gods are invoked. For the Fon people, the primacy of Eshu (whom they call Legba) comes about through his linguistic ability, his proficiency at communicating. In the beginning, Mawu, the female aspect of Mawu-Lisa, the androgynous high god of the Fon, gives her seven children different realms to rule—earth, sea, animals—and gives them a language separate from her own. But she allows Legba, her youngest and most spoiled child, to remain with her and to act as a relayer of information to her children.

So Legba knows all the languages known to his brothers, and he knows the language Mawu speaks, too. Legba is Mawu's linguist. If one of the brothers wishes to speak, he must give the message to Legba, for none knows any longer how to address himself to Mawu-Lisa. That is why Legba is everywhere.[2]

As the hermetic linguist, then, Legba knows the cosmic language as well as the earthly language. This is why humans must ritually acknowledge him before any other god. In our monotheisms, God's information is distant, except for the occasional prophet, and the rest of us are lost in babble and books. But Legba is always traversing that region of babble, and embodies the hope and the peril of a more open channel: hope, because he allows us to speak with the gods and for them to speak with us; and peril, because he tends to play tricks with the information he has, to keep us perpetually aware that he oversees the network of exchange. His nickname is Aflakete, which means "I have tricked you."[3]

In many tales, Legba both causes and solves a power play among the orisha, and he does so by conveying information. In one, Sagbata, the lord of earth, and Hevioso, the lord of sky, are perpetually besting one another, though Hevioso is generally agreed to be superior. Legba lies and tells Mawu that there is no water in the sky, which allows Hevioso to cut off the rain, causing a horrible draught. Then Legba goes to Sagbata and tells him to build a huge fire on earth, which he does. Mawu becomes afraid that the flames will burn even heaven, and she orders Hevioso to make it rain, reducing his prominence and tentatively reconciling the brothers. Among the tales of the Yoruba gods, Eshu similarly propels the narratives of jealousy and power by occupying certain privileged places where he gives ideas and information—not the whole story, but just enough to make the story happen. At one point, Shango the thunder god asks him, "Why don't you speak straightforwardly?" "I never do," Eshu responds. "I like to make people think." [4 ]

Perhaps the most famous Yoruba story about Eshu concerns two inseparable friends who swore undying fidelity to one another but neglect to acknowledge Eshu. These two friends work on adjacent fields. One day Eshu walks on the dividing line between their fields, wearing a cap that is black on one side and red (or white) on the other. He saunters between the fields, exchanging pleasantries with both men. Afterwards, the two friends got to talking about the man with the cap, and fall to violent quarreling about the color of the man's hat, calling each other blind and crazy. The neighbors gather about, and then Eshu arrives and stops the fight. The friends explain their disagreement, an Eshu shows them the two-sided hat—all this to chastise the friends for not putting him first in their doings. The lesson of the tale is obvious, but just as interesting is where it places the god. Moving along the seam between two different worldviews, he confuses communication, reveals the ambiguity of knowledge, and plays with perspective.

So Eshu is a master of exchange, or crossed purposes, of crossed speech. This is why his shrines are found both at crossroads and at the market, for he is master of such networks of desire. For example, he uses his magician's knowledge to make serpents that bite people on the way to the market, and then sells them the cure.[5]

The Fon have a wonderful way of imagining Legba's mastery of crossings. Mawu tells the gods that whoever can come before her and simultaneously play a gong, a bell, a drum, and a flute while dancing to their music would be chief of the gods. All the macho gods attempt and fail, but Legba succeeds, not just demonstrating his agility, but his ability to maintain a balance of crossed or contrary forms and forces (and incidentally providing a window into the unique genius of African music and rhythm). Legba dances not only to the beat of a different drummer, but to the beats of many different drummers at the same time.

As Robert Pelton writes in his excellent book, The Trickster in West Africa (the source of many of these tales), the Fon are "dazzled by [Legba's] metaphysically fancy footwork because they know that the pathways of new order that he opens always skirt the edges of chaos."[6] The creator of plots, the player of many instruments, the trickster Legba always risks unleashing a Pandora's box of powers. But it is only in risking such chaos that novelty is continually reborn, and the community is imagined to interact dynamically, rather than by some rigid structure. The potential for dynamic chaos is the metaphysical heart of the Trickster. There is a Yoruba prayer that goes:

Eshu, do not undo me,

Do not falsify the words of my mouth

Do not misguide the movements of my feet.

You who translate yesterday's words

Into novel utterances,

Do not undo me.[7]

Eshu can transform the past into "novel utterances" because he knows that the power of ambiguity and the multiplicity of perspectives can change the fixed into the free. New connections always create a new world, and Eshu/Legba puts creative chaos in the heart of tradition and shows what advantages can be taken of it. As Pelton states, this god "finds in all biological, social, and metaphysical walls doorways into a larger universe."[8]

Of all the lines that Legba transgresses, the most visible ones are sexual. He is young, small, and spry, and has a ravishing sexual appetite. When Mawu punishes him for some transgression by commanding that his penis remain always erect, he smiles and immediately begins groping the nearest female. In another episode, after tricking many suitors out of deflowering the daughter of a king, he has sex with the woman himself. The happy king commands that Legba may sleep with any woman he chooses, and names him "the intermediary between this world and the next. And that is why Legba everywhere dances in the manner of a man copulating."[9] His priests, the legbanos , even mimic copulation with wooden phalluses.[10]

Since the Fon insist on the primacy of humanity in all its aspects, we err in seeing in Legba's more human behavior the limits of his divinity. For sexuality expresses the trickster's need to always go beyond boundaries: new order is always created out of the partial collapse of a previous structure. More profoundly, copulation is the most fully experienced of connections, Legba's pet project everywhere. These two functions are deeply related, and Legba puts sex in the heart of spirituality, not as transcendent tantra, but as the more immanent principle of connection. Of course, Legba's sexual appetite causes just as much trouble as his propensity to tinker with data, as in the following:

We are singing for the sake of Eshu

He used his penis to make a bridge

Penis broke in two!

Travellers fell into the river.[11]

Eshu makes us recognize the fundamental relation between sex and the evolving, continually reconnecting cosmos. As Pelton writes, "He is the living copula, and his phallus symbolizes the real distinction between outside and inside, and the wild and the ordered."[12]

Garbling the Book of Fate

The Legba of the Fon cannot be correlated exactly with the Eshu of the Yoruba. For the Yoruba, Eshu can be a nastier, more malevolent being, though he still delights in contradictions, and, to a lesser extent, sex. Where there is confusion or arguments, he is there. The violence and lawlessness of Eshu's desire is demonstrated in an a tale related by Robert Farris Thompson about Eshu-Yangi, the father of all Eshu. (Like most orisha, Eshu exists in a countless multiplicity of individual aspects.) Eshu's mother offers him a bounty of fish and fowl, and Eshu eats it all, and, not sated, eats his mother as well. But Eshu's father — in this tale Orunmila, the god of divination — is ready for his hungry son when he came for papa with slavering jaws agape. Orunmila hacks Eshu into little bits, which fall all over the earth, becoming individual shards of laterite stone. Orunmila catches the remaining spirit of Eshu, and to placate his father, Eshu promises that all the stones will become Eshu's representatives. All Orunmila has to do is bless the stones, and they will do his mystic bidding. Eshu then coughs up his mother.

In this tale of cosmic give-and-take, reminiscent of the ancient Gnostic notion of the "shards" or "sparks" separated from the deity, Eshu demonstrates both his generosity and his caprice. For the Yoruba, Eshu is the god who has access to ashé (literally meaning "so be it"), the immanent (but morally neutral) power of creation which the supreme being gives to the earth, and which can be possessed by some people.

Eshu receives ashé when all the gods journey to the supreme god to find out who is the next most powerful. Each brings a huge sacrifice, carrying it on his or her head. But Eshu consults the oracle before he goes, and finds that all he needs to bring is a bright red feather set upright on his forehead. When the supreme being sees this he grants Eshu the power of ashé, because Eshu had shown his unwillingness to carry burdens, as well as his sensitivity to the power of information. (To this day, Eshu figurines often have a large phallic plume or nail on the head.) As Thompson says, Eshu shows us that one must "cultivate the art of recognizing significant communications...or else the lessons of the crossroads—the point where doors open or close, where persons have to make decisions that may forever effect their lives—will be lost."[13]

Of course, these moments of crisis, of significant communication, are oracular moments, and it is appropriate that Eshu has a subtle and complex relationship with the Yoruba (and, subsequently, Fon) system of divination, Ifa. The process of the divination itself is eerily similar to that of the I Ching: The babalawo, or diviner, quickly passes sixteen palm nuts between his hands, and depending on how many are left, he draws either a broken or solid line in powder. He (and the babalawo is always a he) draws two groups of four lines each to create one of 256 possible patterns. He then recites from memory the numerous verses associated with that odu, and he and his client will settle on those verses which seem relevant. (Like the hexagrams of the I Ching, the verses are often ambiguous and enigmatic.)

Because Eshu is the ties between cosmic pattern and daily life, it is obvious why he would be associated with divination. Like the kabbalistic Tree of Life, Ifa is described as having "roads," "pathways," or "courses," resonant linkages of images and meanings — obviously Eshu's bag.[14] For the Fon, whose system of Fa divination is very similar to the Yoruba's Ifa, Fa is destiny, the pattern of the day, the individual and the cosmos. Each person has an individual Fa, just as each person has an individual Legba. Because Legba is the only god who knows the "alphabet of Mawu," he is "sent by Mawu to bring to each individual his Fa, for it is necessary that a man should know the writing which Mawu has used to create him."[15]

Sometime before Ifa existed, a Yoruba myth goes, a declining human race had stopped sacrificing to their gods, and the gods were hungry. So Eshu decided to give humans something that would make them want to live. He journeyed to a palm tree, and there the monkeys gave him sixteen palm nuts and told him to go around the world so that he might hear "sixteen saying in each of the sixteen places." He did so, and then gave the knowledge to men through Ifa, the "sixteen places" being the sixteen primary odu and the sixteen palm nuts. This myth again demonstrate the reciprocal relationship between man and gods; it is said that without Eshu, the gods would always go hungry, for he tricks men into disastrous defiance so that they will then need to sacrifice to win back the gods' favor. But it also emphasizes Eshu's character as a mediator and a speedy messenger, who places himself between different perspectives and collects messages.

Legba's relationship with Fa, and Eshu's with Ifa, shows an extremely subtle and lively understanding of divination and destiny. Eshu gives the world Ifa, and on the babalawo 's divining tray, twin Eshu statues stare out at each other (again, like Hermes, Eshu is linked to twins). But he is not Ifa's master. In one Fon tale, Fa, the god of divination and fate, sneaks into Legba's home and sleeps with his wife. Legba asks her why and she says that his penis wasn't big enough for her. Challenged, Legba eats an enormous amount of food and swears to have sex with her until she tires, all the while calling out "the path of destiny is large, large like a large penis."[16] Legba then made Fa stay in the house, while Legba takes his wife and hits the road, vowing that he will always be first, and will always be ready to fuck.

As Pelton writes, "Fa keeps a certain dominion over destiny, or inner space, but Legba's elasticity gives him mastery over destiny's paths...Legba can roam as he chooses, going in and out to bring men to their destiny, but never ceasing to widen the path for them."[17] By knowing the whole system, Eshu can escape, slipping through the cracks of fate. Eshu's Ifa odu is the seventeenth, the first one outside the system.[18]

Why is Eshu/Legba linked to divination? Because, paradoxically, freedom is tied to divination, if only for the simple fact that oracles must always be interpreted, its messages decoded. As Eshu makes abundantly clear, such decodings are always ambiguous and partial. The literary critic Henry Louis Gates, Jr., whose Signifying Monkey uses Eshu to establish a model of African-American textual analysis, says that at the crossroads "there is no direct access, or contact, with truth or meaning, because Eshu governs understanding." And Eshu is a tricky governor, whose pathways of information are always surrounded by the mud of ambiguity.

New Wordly Wisdom

When the orisha were smuggled to the New World on slave ships, they changed their character as the concrete situations of their followers changed. Mixed together, cut off from traditional structures, surrounded by Christianity and the whip, New World Africans now had different spiritual needs. The world's most vibrant form of syncretism emerged, where Catholic saints and the orisha blended into one another, and the worldly wisdom of West Africa continued disguised in song, drum, and celebration. Eshu himself went through many changes, and while different geographical groups of African descendents took him in opposite directions, all of his varied faces nonetheless further extend his peculiar multivalent being.

In Brazil, Exu — as his name is written in Portuguese — become a darker being. In condomble, Brazilian orisha worship, Exu rules over sexual intercourse and is still served before any other god is invoked. But this is not so much to open up a divine communications channel as to placate the irascible deity and make sure that he does not spread confusion.

Eshu's emphasis on trickery and vengeance made him an ideal orisha for slaves, who imagined him as the saint of revenge against the whites. Under these conditions, his more malevolent aspects were emphasized, as his various aspects were multiplied to cover a range of nasty magical acts. In umbanda, the urban, highly eclectic revision of condomble that relies heavily on nineteenth-century spiritualism, Exu quite simply becomes the devil.

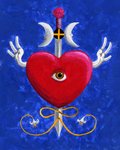

In Haiti, where the orisha are known as the loa and the practice is known as voudun, Legba went through other drastic changes. He is still lord of the crossroads, the grand chemin, whose channel between earth and the gods is contained in the ritual house's peristyle, or poteau-Legba. The crossroads is seen in Legba's vévé (a complex cosmic diagram drawn with white flour that represents the loa). But in Haiti Legba has become an old, withered peasant, bent and crippled on his cane. In her superb Divine Horsemen, the American avant-garde filmmaker Maya Deren tells how terrible and twisted the possessions performed by Legba are. In Haiti Deren describes a Legba who comes full circle, like the answer to the riddle of the sphinx, no longer the virile child of the morning but the impotent old man of evening. He is still the omniscient observer — as one Haitian told Deren, "We do no see him, he sees us. All those who say the truth, he is there, he hears. All those who speak evil, He is there, he listens."[19] But his omniscience has become the knowledge of death.

As with Brazil, the Haitian Legba is known for his magic. One prayer goes "Sondé miroir, O Legba," which means literally "fathom the mirror" and figuratively "uncover the secrets."[20] As with most Haitian loa, Legba has two main aspects: a Rada and a Petro, the Petro being darker and more frightening. Legba's Petro aspect is called Carrefour, the crossroads, and he is lord of black magic, linked to Ghédé and Baron Samedi, the fearsome baddies of death and the grave. Legba's sacrifice is a white cock whose neck is twisted; Carrefour gets a black cock who is set on fire and allowed to run around in agony. While Legba's vévé emphasizes the four distinct cardinal points of the metaphysical axis, Carrefour's emphasizes all the wayward points in between. But Carrefour's magic is for man to use, to ward of demons or run the risks of invoking and using them. Wisely, the West African tradition puts the onus on man, not some transcendent deity; as Deren points out, it is man who makes magic, not the loa.

In Haiti and Cuba, Legba is not the devil, but is syncretized with other saints, particularly St. Anthony, St. Lazarus (who is old and walks with a cane), and, sometimes St. Peter, the gate-keeper. Again, these correspondences are not fixed in stone, but seem to mutate as the context of the world changes. This ability to adapt shows the deeply pragmatic wisdom of orisha worship, for, as esotericists know, all great magicians are revisionists, not classicists. But for all his different aspects, forms, and Christian names, some followers of the orisha insist on the central unity of the Trickster figure. Molly Ahye insists there is no difference between Haiti's Legba and the Trinidadian/Brazilian Eshu:

Eshu is Legba, Eshu-Elegbara. Legba is a contraction. Eshu is the connection, the spiritual connection between man and divinity....Eshu is a mirror of us. He embodies all the forces, positive and negative. Eshu is the one who guards the secrets. He has the power to manipulate man or to free man, because there is so much of man in him. You are linked to him by your humanness and he plays on that. And you are linked to him by your divine spirit and he tests that...How do you know you're good and righteous if you haven't passed through the fire? What is the force that will test you through that fire? Even is that thing has to bear your weight — infamous, evil, whatever — that is the thing that gives you the opportunity to test yourself. That is what Eshu does.[21]

A Little Legba in Us All

As is probably apparent, I feel that in Eshu/Legba we meet one of the world's most impressive gods. His lawlessness and tricks not only keep us on our toes, but point us towards the most creative components of destiny, the free zones of fate. In him, the Trickster becomes a kind of metaphysical principle. While never losing touch with the ground, he wanders perpetually, in search of information or sex. For Pelton, Legba embodies Jung's synchronicity, and for Henry Louis Gates, he is the Logos. But Eshu is also the being of the network, of the immanent language of connection.

The orisha are not frozen, static patterns of tradition, nor do they exhibit the more reactionary tendencies found in overly transcendent, patriarchal models of spirit. As a result, these "living" gods are able to continually come to terms with the world as it is for people now. The character of Papa La Bas in Ishmael Reed's Mumbo Jumbo is no less real a Legba than the ones in anthropology books, or the one Robert Johnson met and sang about in Mississippi. In his book Count Zero , science fiction writer William Gibson put the orisha in the heart of cyberspace, his computer-generated astral data plane, and it worked far better than any hoary Egyptian deity or Irish fairy would have. Gibson, who tossed in those gods when he was bored with his book and happened to open a National Geographic article on voodoo, told me in an interview that he felt "real lucky, because it seemed to me that the original African religious impulse really lends itself much more to a computer world than anything in Western religion...It almost seems as though those religions are dealing with artificial intelligence.". Gibson also pointed out how similar vévés are to printed circuits.

While Gibson was talking about fiction, what he's saying demonstrates the contemporary appeal of the orisha to folks who may not willing to kill cock with their bare hands. And of all the orisha, Eshu hints at the most profound, and relevant, connections: between networks and truth, magic and perspective, messages and sex. Of all the orisha, he is the one that speaks most to non-devotees, because he is about the very process that we go through in order to hear him: the process of communication.

Sanpwel is not a Vodou religious phenomenon,

Sanpwel is not a Vodou religious phenomenon,