Voodoo, Religion and the 'DNA of American Music'

![]() View a photo gallery from Burnett's West Africa voyage

View a photo gallery from Burnett's West Africa voyage

![]() Radio Expeditions: West African Voodoo

Radio Expeditions: West African Voodoo

Feb. 5, 2004 -- Correspondent John Burnett has traveled the world covering news stories for NPR -- usually, reporting on wars, politics or natural disasters. But in this Reporter's Notebook, he describes a more spiritual journey. As part of a joint effort with National Geographic called Radio Expeditions, Burnett traveled to West Africa to explore the roots of a religion seemingly as old as humanity itself:

We had been advised that in order to attend the Epe Ekpe voodoo festival as observers we would need to "go native." That meant sheathing ourselves in white togas, which would be a show of respect for the voodoos, or spirits, also present.

The role of music in voodoo was something for which I was completely unprepared. It erupts from voodoo adepts, or believers -- indeed, it erupts from West Africans in general, like water from an aquifer, deep and pure and bracing. Josh Rogosin and I were profoundly moved by the beauty of the music.

So on the midnight before the celebration, in the Togolese village of Glidji, all 10 of us -- me, NPR audio engineer Josh Rogosin, as well as an anthropologist, a still photographer, the National Geographic Channel film crew and a couple of Italian translators -- all pulled off our clothes and wrapped ourselves, John Belushi style, in white muslin cloth.

When we stepped out of the fetish priest's house into a large courtyard, dozens of local women burst out laughing. It was the only logical response. We looked preposterous. I wondered at that point if it wouldn't be more of a sign of respect to the voodoo gods if we were allowed to put our shirts back on.

Throughout our nine-day stay in West Africa, we were welcomed into voodoo ceremonies, private homes and private lives with unfailing courtesy, sincerity and openness. Africans genuinely wanted us to see how they worshipped this ancient religion known in the lengua franca as vodun.

We discovered that voodoo -- as it is known in the West -- has little to do with sticking pins into dolls. The involvement of "black magic" sorcery appears to be a real but minor aspect of the entire belief system.

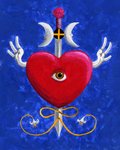

At its heart, voodoo shares the same objectives of other faiths: to seek success in one's life through divine intervention. But instead of lighting a candle and praying to St. Jude, believers make an offering to Legba, the protector spirit (Legba's hard to miss – he's the statue with the giant wooden phallus).

In the 25 countries from which I've filed stories for NPR, I've had the opportunity to visit many indigenous cultures. But nothing prepared me for the spectacle and pageantry of Epe Ekpe. The whole gathering was suffused with a profound sense of holiness.

In one gathering, a woman splashed sanctified water onto a circle of people anxious to receive blessings, as well as relief from the sub-Saharan heat. Exquisite drumming and singing and chanting broke out spontaneously from knots of believers. Women fell into trances, shrieking and barking as the spirit of their particular deity entered them. But as the afternoon wore on, there was nothing scary or particularly freakish about the practice.

As a journalist for nearly 25 years, it was refreshing to be traveling to a foreign country not to report on death and destruction, but simply to witness and document its religious culture.

It made sense, later, when our colleague, anthropologist Wade Davis (who has one of the coolest jobs I've ever heard of -- Explorer in Residence for the National Geographic Society), recalled a saying he had heard from Haitian voodoo practitioners: "White people go to church and speak about God... We dance in the temple and become God."

For all the authenticity of Epe Ekpe, there is a bogus side of voodoo for tourists. When Josh Rogosin and I went to the famous fetish market in Lome, Togo, we were taken into an interior room by the market chief, a man named Felix who wore sunglasses and seemed eager to please.

We had picked out a couple of fetishes, or charms, to buy from him -- primarily as a courtesy, and a tip, for spending a half-hour giving us a tour of the bizarre market. Then Felix said he would summon the gods on our behalf. After much theatrical chanting and rattling of chains, he threw the cowrie shells on the floor, studied them, then looked at us gravely and said: "I have consulted the spiritual powers. For the big fetish, you pay 11,000 francs, the small fetishes, 4,000 each one." He could have made a good televangelist.

The role of music in voodoo was something for which I was completely unprepared. It erupts from voodoo adepts, or believers -- indeed, it erupts from West Africans in general, like water from an aquifer, deep and pure and bracing. Josh Rogosin and I were profoundly moved by the beauty of the music.

On our first night, our tour guide, a former Catholic priest named Roberto Cerea, asked a group of young people to come and sing for us. As we listened to the complex, polyrhythmic drumming and their soaring unison singing, my eyes started to tear up. At that moment, National Geographic photographer Chris Ranier, a gifted artist and wise traveler, leaned over to me and said -- as if apprehending the thought I was trying to form: "This is the DNA of American music."

The three-part Radio Expedition report on West Africa's spiritual traditions will be broadcast February 9-11 on NPR's Morning Edition.

No comments:

Post a Comment